I’m a User experience architect or UXA. UXAs are part of the BBC design team, but it’s a job title that can sometimes be difficult to decode – as I’ve learned when trying to describe what I do to family and friends. It’s fairly easy to imagine what a designer might do, but a user experience architect is a little less obvious. I wanted to share what UXAs do and talk about some of the projects I’ve worked on recently.

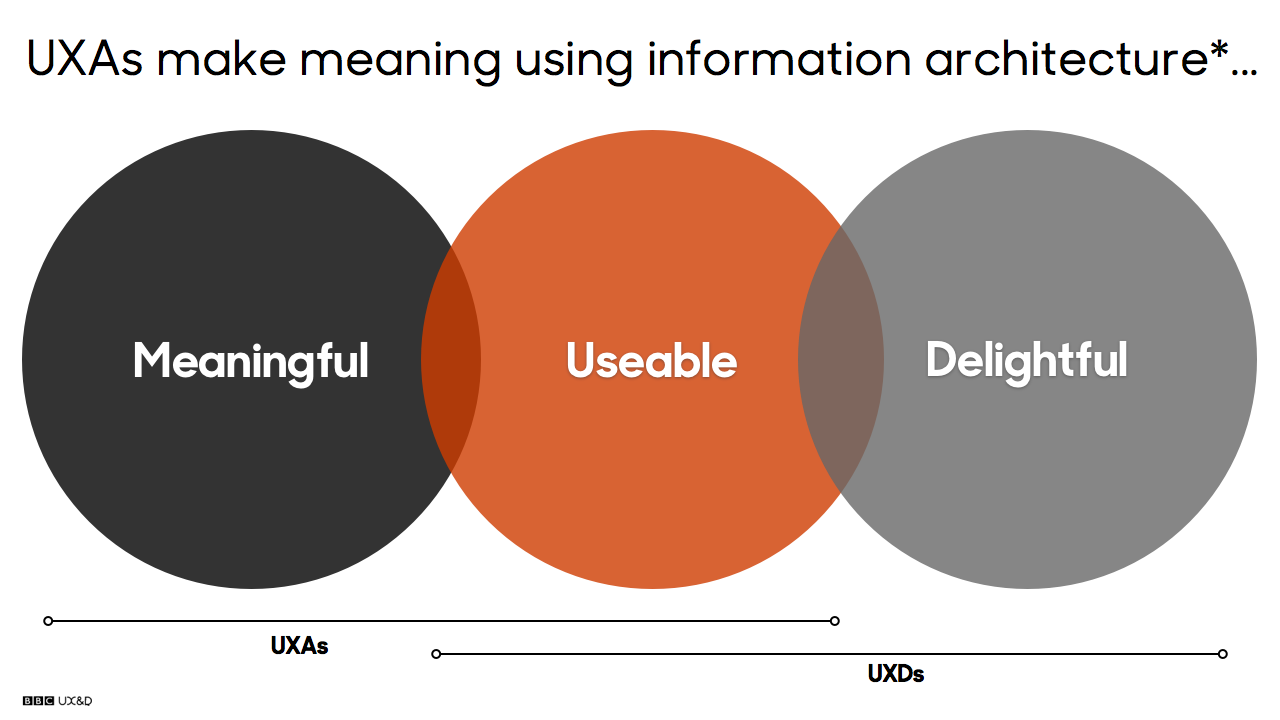

I work at the BBC, and until last year UXAs were called information architects. Information architecture is still a big part of what we do. There are lots of definitions of information archiecture, but I like the one that describes it as ‘the art and science of organizing and labeling web sites, intranets, online communities and software to support usability and findability’. In the real world architects have been making physical spaces make sense for hundreds of years. Now that we build virtual spaces online, information architects try to do the same. We try to make information spaces meaningful, as well as useable and delightful.

We make meaning using a variety of tools and techniques, and there’s lots of variety to the way UXAs work. But we all of try to contribute a certain type of thinking to the projects we work on. The effect that we have on a project will usually fall into a few categories, so I wanted to write about a few projects and show what UXA-thinking brought to the project. There are different ways of classifying the impact a UXA can have, but I thought I’d use some categories introduced by Andrea Resmini and Luca Rosati in their book Pervasive Information Architecture: Designing Cross-Channel User Experiences.

UXA’s make meaning

Making content that is ‘resilient‘ is one of the priorities of a UXA team. We work hard to understand content and the parts that it can be broken into. We’ll often create a model of the content, describing the parts and properties so that we understand how we could change the shape and adapt the content to different devices and contexts. We’ll often map user journeys, trying to understand all the places a user might encounter a piece of content. For example, we might discover we can reuse the same content titles for page titles, to create promotional units, in our mobile apps and in search engine results pages. By thinking carefully about the way our content will need to adapt, and all the places it can appear we can make sure it’s fit for purpose.

This brings us to the second concern of the UXA – reduction. We want to reduce stress and frustration and make sure the sites and tools we design are efficient, both for our audiences and for content creators. Just like the plumbing and wiring are usually hidden in physical architecture, we’ll work hard to make things as simple as possible for our users. We work hard to identify where things are the same and where things are different. We try to control dependencies within projects and technology by identifying difference. And if ever there is a chance to reduce the complexity of something, a UXA will usually argue for it.

This interplay between things that are the same and things that are different is seen in our third concern – consistency. UXAs work hard to make complicated things more meaningful. Thinking about reduction and resilience help with this, but consistency also plays a big part. You can see UXAs designing for consistency across the BBC. From URL designs sharing similar patterns and permanent IDs, to creating controlled vocabularies to ensure that content is tagged and described consistently, we create internal and external coherence by establishing principles and basing our design decisions on them.

Correlation is the fourth goal that we aim for. UXAs work hard to form connections between our content, connections that enable goal-completion and meet user needs. We bind content together, creating ontologies and taxonomies to describe content and relationships between content and products. For example, I worked on the BBC curriculum ontology used to describe and group learning content in the same way the national curriculum, teachers and students think about it.

UXAs will often carry out ‘card sorting’, working with our audiences to ensure the way we’re tagging and describing content matches what they would expect. I also worked on ways to describe and connect iWonder guides, so that once you’ve found one piece of content you like you can continue your journey to related content that will inform, educate and entertain.

The final goal of the UXA is probably the hardest to describe, but the most important. Placemaking is our attempt to create information spaces on the web with the same sort of inherent meaning as well-architected places in the real world. Badly-designed websites can feel confusing and frustrating. Without the equivalent of landmarks that exist in the real world, navigating ‘information spaces’ can feel disorientating. UXAs work hard to make sure you can find the content you’re looking for and can easily navigate around the places where the content is found.

We’re also increasingly trying to connect the places we’ve created online. For example, I’ve thought hard about how we could eliminate seams between iPlayer, BBC News, iWonder and other parts of the BBC online. Good UXA work should enable the user to focus on the content and move effortlessly around a site to find the content you’re interested in. Creating sitemaps and identifying the underlying structures behind our sites helps us to look for opportunities to create ‘places’ online, and we work with designers to make this structure discoverable and understandable as you move through our sites.

I’m hoping this has given a good introduction to the type of work UXAs do. I’m also hoping that the next time someone asks me what a UXA does, I can just point them to this URL – thanks to a UXA it should still be here the next time someone asks.

Leave a Reply