This is a talk I filmed for an event in November 2022. It focuses on the challenges of effective collaboration and covers ideas around: – the zone of uncomfortable debate – humble inquiry – crucial conversations – and negotiation tips from Never Split the Difference. It’s all strung together from a memory I have of watching a film version of The Emperor’s New Clothes.

Here are some references and (affiliate) links to books:

Humble Inquiry: The Gentle Art of Asking Instead of Telling Instead of Telling

Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High, Second Edition

https://blog.som.cranfield.ac.uk/knowledge/creating-a-safe-space-for-zoud

Here is the text of the talk:

When I was around nine my Gran gave me this film on VHS, and perhaps because I watched it over and over again it got into my head – probably like most of us, I enjoyed the story of the Emperor’s New Clothes – and it might have shaped how I think about the world.

Now… in that sentence there are a few assumptions – let’s clear them up:

1. I have assumed you know what a VHS is… well, it’s sort of like a big tape with a film stored on it… sort of like a DVD. And maybe I’m even assuming you know what DVD’s are… they’re like a bit of Netflix saved onto a physical drive. Netflix used to send them in the post before streaming… but, anyway, you can’t stream this version of the story…

2. and that’s my second assumption I assumed that you know and like the story of the Emperor’s New Clothes.

Assumptions are easy to make… but, like other forms of invisible information, they can form barriers between us.

The version I watched version of that story is a comedic take. There’s a criminal who has a plan to extort money from the monarch, there’s a love story, there’s comedy, there’s singing. There’s really bad acting.

I remember one song in particular about halfway through the film.

The criminals have started making these clothes for the king and they’ve said that only intelligent people can see the clothes. But the clothes don’t really exist. The song features his two key advisers debating over whether the clothes are red or blue… they both have a favourite colour and are convinced that the clothes that don’t exist and which no-one can see reflect their preference. In the story it takes the innocence of a child to burst the bubble and point out how silly everyone, including the all powerful emperor, is being.

I think I remember watching this film, enjoying the singing and comedy but thinking, “well this is clearly a farce made for children, this would never happen.”

And then I’ve lived my professional life and sat in rooms and sort of seen that song re-sung in different voices and at different tempos again and again as people advocate with certainty that excludes other possibilities and express arguments made mainly of bias, prejudice or preference rather than facts and data.

I’ve also sat in other rooms, with teams as people react like the King in that story and are held back by pride or a lack of confidence and so take things for granted and don’t ask questions that they’re dying to know the answer to… like can anyone else see these clothes?

Sometimes the environments we create for collaboration hold people back – and just like in the story of the emperor’s new clothes, it takes confidence and curiosity to burst the bubble and get people who might have been blinded by a little too much confidence and too little curiosity to ask “what if…”

Today is about breaking down barriers and I want to convince you that the most dangerous barriers are the invisible ones.

They’re most dangerous because they’re harder to make intentional choices and interventions around, because we miss them.

We create invisible barriers when we miss something obvious because we don’t question it, or when we take something for granted, or when something stops us questioning – a fear of being wrong, or slowing things down or looking silly.

Finding these barriers and either breaking them or navigating up and over them or around or under them is some of the most valuable work that we can do.

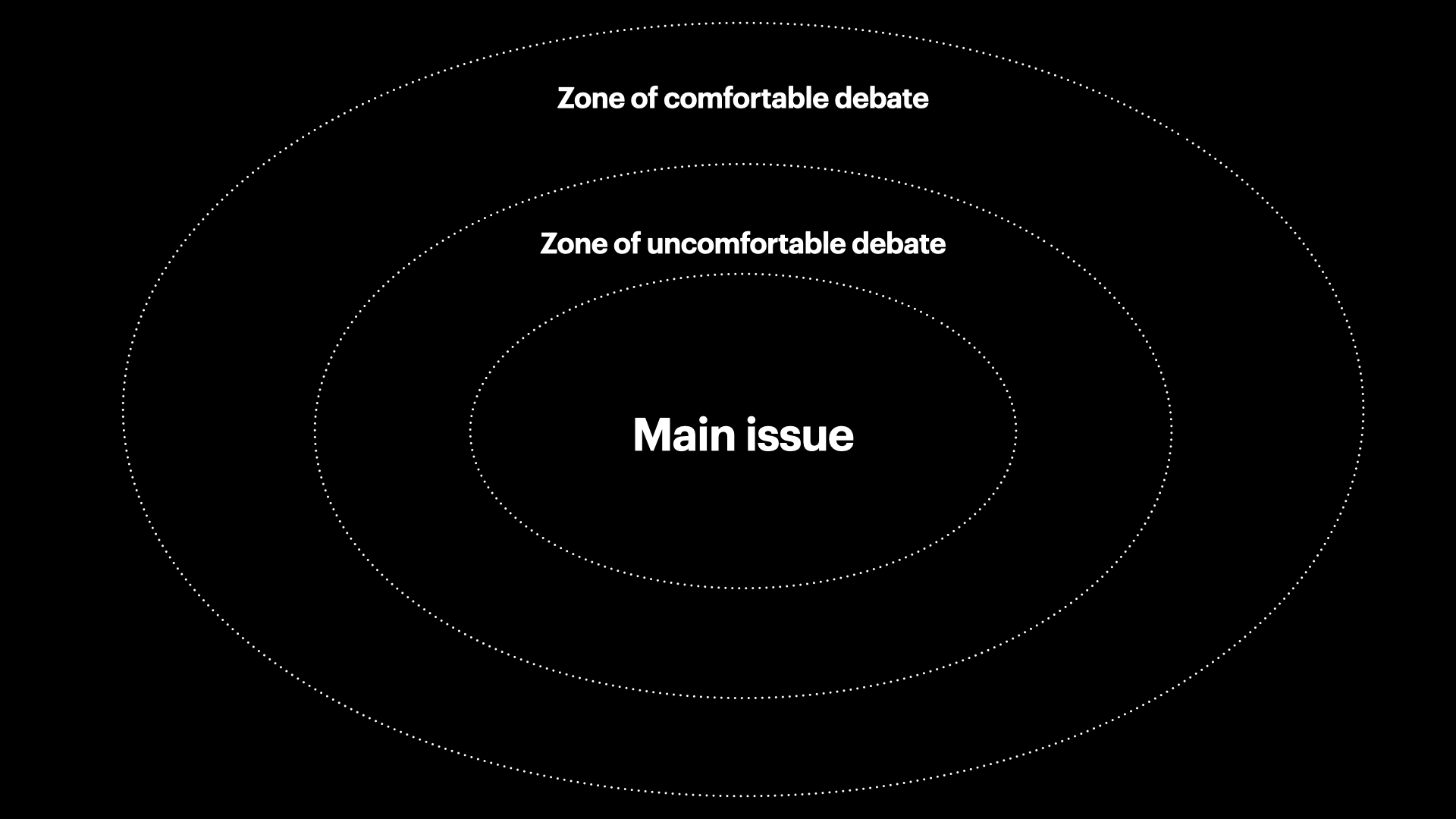

So that is our main topic, our big issue… and I want to start with how sometimes, the big issue, the main thing we need to resolve is the hardest to address.

Sometimes, talking about the most important thing is difficult and challenging, particularly when it’s contentious and there isn’t agreement. Issues like, what gets into the Minimum viable product, what feature should we prioritise in the next sprint… these can be the things we need to address.

But to talk about them we find ourselves in this ‘Zone of uncomfortable debate.’

At it’s best this is a zone of constructive dialogue and debate about ideas. But it can be uncomfortable because we might not have enough information, or we might have to resolve differences of opinion. This is uncomfortable and if we don’t navigate this zone with skill and intention it can erode our relationships of trust which make collaboration effective.

At other times, even when we know what the big issue or the most important topic to discuss is, and we know that we need to resolve some uncomfortableness like differing priorities or opinions, we spend time talking about other things – talking about the things we already agree on or the things that don’t really matter or make progress. This ‘zone of comfortable debate is where we’re talking about things that feel safe – the things that we already agree on, in Britain we might talk about the weather. But they don’t always add any value.

I like this model – I think it gets us thinking about lots of things that are important for team work and collaboration. The differences in these zones hint at the importance of psychological safety – that is the belief that you won’t be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes.

It also hints that the level of safety can fluctuate through interactions and relationships – that’s why I like to flatten this model into a line or area diagram, rather than the radial one.

This helps me think about how meetings, projects and relationships can spend different times in each of the zones… I think over time we tend to build the trust and shared language that allows us to spend more time talking about the real issues, addressing issues and shrinking and becoming slighly more comfortable and much more skilled in the zone of uncomfortable debate… I also think that sometimes we need to spend time in the comfort zone to recharge – and there are other movements and patterns of behaviour that we can observe and diagnose using this “map” which might help us collaborate.

So let’s pick a few of them…

1. The investment – this behaviour sees us consciously spend some time here, just on the boundary of comfort. We can use small talk and active listening to hear the things that matter to people we work with, which are revealed when people are relaxed. Take note of preferences. How do people think? Do they speak in metaphors? Do they like data or statistics – this is their default style. Spending time here builds trust and insight. And we can use that as we enter more uncomfortable interactions. Talking of which…

2. You are here markers – when you’ve entered the zone of discomfort, identify it. The initial awkwardness will feel hard, but usually it will make the discussion more fruitful. We can use “Process moves” in feedback conversations – things like “I’m feeling tense” to highlight where you are emotionally. This can humanise the moment and break barriers.

3. Bridge to the issue – This forms a smoother transition into the zone of uncomfortable debate. Saying things like“This might be a difficult conversation.” Can sometimes help. Occasionally this can backfire – as it primes people for a certain type of interaction. But if you have trust this is usually helpful, rather than disruptive. And by identifying and calling out that there might be differences of opinion, it moves them into the light so they’re easier to address and people can spend more time on the issue, rather than trying to parse subtext.

4. The retreat – happens when people go back to comfort without making a decision. This can go on for a long time and can mean that the real issues are never addressed. So this can be unhelpful, but you might be able to transform a retreat into a ping pong

5. The ping pong – occurs when people intentionally move back and forth so they can recharge… later I’ll talk a little about techniques from negotiation. Summarising can be one for of ping pong – it takes stock of where we are in a safe way before returning to points of contention. You can create moments where everyone can use the recharging effect of comfort to give the group the safety to have another go at the difficult debate… but try to make sure that you reach decisions or actions.

So those behaviours might be useful, they’re what you can do when you’re navigating the zone and they provide labels for some behaviours that might be useful… but how do you actually do that, practically?

The most important skill in overcoming assumptions, confusion, ambiguity and other types of invisible barrier is usually doing it authentically – sharing your own perspective to contribute to the group.

You’re there for a reason and by making a contribution you will move things forward.

But there are a range of styles you might like to adopt when you find yourself in this type of team or collaboration.

I’m going to quickly touch on three approaches – obviously, we haven’t got lots of time today so take these more as useful tips and book recommendations rather than definitive explanations of an idea or approach.

But there are different approaches that we can take when we find ourselves in uncomfortable conversations and I’m going to talk about:

- one focused on questions,

- one focused on clarifying

- and one focused on negotiation…

I hope that by sharing a few you’ll find the ways that work best for you… and actually thinking of these as building blocks will make you more successful.

Humble Inquiry

This section is about the difference between inquiry and advocacy.

Let’s just take a moment to think about how we respond when someone is talking.

What do you do when someone is talking? Are you listening or waiting for your turn to speak? What do you do when someone asks a question? How often do you ask questions?

I think questions are a super power – even rhetorical questions can get us all thinking in a certain way and exploring possibilities.

In The Emperors New Clothes, the king is humiliated because he has no humility. And he doesn’t ask the right questions – he doesn’t really ask any questions. This can happen to all of us when we’re sure of our expertise, or convinced of our position or when we’re under pressure.

Pressure tends to create a fight of flight reaction that literally shrinks the options we can perceive… And we also have a whole heap of cognitive biases which can combine to shrink the potential that we see in situations and form invisible barriers that stand between us and other people.

This is how most of us make sense of the world:

Prior experience forms expectation filters the data we receive.

We see and hear more or less what we expect, based on prior experience, or, more importantly, on what we hope to achieve.

Then we react. And there’s growing evidence that emotional response may actually occur before or at the same time as observation. People show fear physically before they perceive the threat.

It is essential for us to be able to know what we are feeling, both to avoid bias in responding and to use feelings to help us diagnose the situations we find ourselves in. If we’re feeling tense – a meeting will feel tense. If we’re feeling defensive, we might compromise our ability to listen and respond.

Judgement and action are only as valid as the data it’s based on.

So we need to minimise distortions in input.

ut one way of minimising this filtering and short circuiting effect, and breaking down the barriers they create, is by adopting a more curious and humble position as we collaborate. So, we need to understand two things – humility and inquiry… let’s start with humility.

There are a few types of humility and depending on our role in a team we might need to flex how we adopt a position of humility.

There’s Basic humility where humility is not a choice, but an arbitrary condition, like social status or your position in a team or organisation.

Optional humility where we feel humble in the presence of people who have achieved great things or are experts in their field.

Here and now humility occurs when I am dependent on you for something.

Collaboration creates interdependence – so humility should be something you can adopt in a team, even if you’re leading it.

Combining humility with inquiry maximises our curiosity and that’s a super power to minimise bias and preconceptions and genuinely collaborate with other people. It shuts down fight and flight responses and allows us to access our ignorance and accept it.

There are different types of enquiry – but when we add humility to them they become even more effective.

Diagnostic inquiry is when I’m curious with a specific focus or agenda. I steer and influence the other person. There can be a number of different diagnostic focus points:

- Feelings and reactions focus others on their feelings and reactions (they might not have considered these or feel inquiry in this area appropriate)

- Causes and motives co-opts the other speaker into delving into interpretation or analysis

- Action oriented ask what they did or are planning to do in the future. A convergent style of questioning asks people to focus on what is to be done.

- Systematic questions build understanding of the total situation

Confrontational inquiry sees you insert your own ideas in the form of questions. Rhetorical questions and leading questions fall into this bracket. These may still be based on curiosity, but it’s now in connection with your own interests. You now want information related to something you want to do or that you’re thinking about. The same four categories can apply eg:

- Feelings and reactions – “Did that not make you angry”

- Causes and motives – “Do you think they sat that way because they were scared?”

- Action oriented – “Why didn’t you say something?”

- Systematic questions – “Were the others surprised?

Process oriented inquiry might also be called ‘process move’ which ask about the conversation or inquiry itself. For example, ’Did I offend you?’ Or ‘Is it OK to talk about this stuff today?’

You can use different forms of process based inquiry. Compare:

- Diagnostic process inquiry – What should I be asking you now?

- Confrontational process inquiry – Why has what I’ve said upset you?

- Humble process inquiry – What is happening here?

These are useful in feedback conversation – which I’m going to talk about next.

I think adding a little slice of humility to every form on inquiry makes it more effective – and improves your chances of navigating the zone of uncomfortable debate.

But there are thing that make this more difficult and make the zone more unc omfortable…

- cultures of ‘telling’ – especially as an expectation of leaders push people into feeling uncomfortable because we take away their autonomy and can compromise their performance and mastery

- teams which only value task completion at the expense of relationship building and

- rules of deference and demeanour associated with rank and position.

These features of work can make things more uncomfortable and make using humble inquiry more difficult.

We see all of these things in the Emperor’s New Clothes story… and we often see it in collaboration as people are more invested in being right or getting their own way rather than establishing and driving towards a common purpose and shared success.

Too many conversations and collaborations see us retreat into our own preferences and perspectives.

But getting the balance right between our own self-interest and the valuable input that others can make is the secret to collaboration… so let’s explore that…

There are lots of reasons why we can fall into the trap of advocacy and miss chances to improve collaboration – sometimes we’re so sure of our solution that we fail to recognise a better one – even if it’s right in front of us.

Situations can conspire to create barriers that obscure possibilities. Some of the barriers occur when we find ourselves in‘crucial conversations’. These are conversations when the stakes are high – when we feel like there is something to be won or to lose… in some ways the criminals in the Emperor’s New Clothes make every conversation a crucial one, because they engineer a situation where people are protecting their pride or position.

Different people react differently in these situations – but the zone of uncomfortable debate is full of these types of conversations. They create heightened emotional engagement and that might spark fight or flight responses. We evolved these responses to keep us safe when we were threatened – and now our brains are tricked into feeling threatened when our opinions, expertise or perspective is questioned.

This can happen in all sorts of interactions when we’re working collaboratively – but feedback conversations can be particularly tricky – because there are invisible barriers that make sharing information more difficult.

When someone gives us feedback it’s easy for us each to be operating in two separate worlds. I understand my thoughts and feelings and my intentions. But the other person usually sees only my behaviour and my impact on them, from this they create their story about me. Their feedback is about their world, but I compare that to my world – my intent and if the two don’t match I can feel threatened, confused, angry and under stress.

According to the Crucial Conversations team, there is a range of 6 styles that people show when they are under stress.

- Masking – Consists of understating or selectively showing our true opinions. Sarcasm, sugarcoating, and couching are some of the more popular forms.

- Avoiding – Involves steering completely away from sensitive subjects. We talk, but without addressing the real issues.

- Withdrawing – Means pulling out of a conversation altogether. We either exit the conversation or exit the room.

These three are styles that tend to lead us away from the main issue and towards the zone of uncomfortable debate. They drive us further away from meaningful collaboration.

The other three styles heighten the tension in the zone of uncomfortable debate and make it more uncomfortable – making progress less likely.

- Controlling – Consists of coercing others to your way of thinking. It’s done through either forcing your views on others or dominating the conversation. Methods include cutting others off, overstating facts, speaking in absolutes, changing subjects, or using directive questions to control the conversation.

- Labeling – Is putting a label on people or ideas so we can dismiss them under a general stereotype or category. I’ll talk about good labelling in the next section – but this is using labels as a weapon.

- Attacking – You’ve moved from winning the argument to making the person suffer. Tactics include belittling and threatening.

All of these three styles can make hte zone of uncomfrotable debate more uncomfrotable and less effective.

So how we do we avoid these behaviours or cope when we bump into them during collaboration?

I find it useful to take a moment and think where I am in a conversation or collaboration. Do we have a shared purpose, do we have relationships of trust, do we have a shared language so that we can communicate effectively? Do I understand what the other person wants or needs.

The key to overcoming invisible barriers is usually the secret to any good design.

- In the early stages, try to frame statements as hypotheses rather than assumptions: Don’t assume, use negotiation to test hypotheses.

- Uncover as much information as possible (don’t prepare a counter argument). Spend time lis tening

- Try to help people feel safe to help them open up and contribute. Cultivate empathy Imagine yourself in the collaborators situation. Recognize their perspective and vocalise/demonstrate that recognition (Ask, mirror, paraphrase, and prime).

- Listen out for people expressing feelings and hear what’s fueling those feelings. Focus your attention on identifying emotional obstacles that are standing in the way of an agreement. This might been analysing people words, tone and body language and spotting changes and incongruence.

You want to remind collaborators that you share a problem – so rather than retreating to different sides of the problem, you need to encircle it so that you can attempt to solve it together.

That doesn’t mean compromising, it means working as hard as you can to find the win:win in every collaboration – where everyone wins.

And that takes us to the final perspective or approach – one based on negotiation.

So, I’ve talked about Humble Inquiry to help us get the balance right between talking and listening. And we’ve used active listening and our communication skills to get information, build intimacy, express our own expertise and perspective and show our commitment to a common goal.

But how do we make sure that we get what we need out of collaboration? Especially when we find ourself in the zone of uncomfortable debate and things get heated or people retreat into their self-interest rather than a shared, common interest?

We can approach it as a negotiation – and one of the best ways of approaching negotiation is from this book. So I want to end by sharing two ideas from here.

The first is the extension of what we’ve been talking about – a heightened awareness of what other people need, and the use of this empathy to make progress.

Quite often in the zone of uncomfortable debate we’ll be faced with a barrage of barriers and negative responses that we need to resolve to make progress. We need to be able to neutralise these negatives. but we shouldn’t avoid them – avoiding negatives has a counterproductive effect on trust and influence – it just moves us back to the zone of comfortable debate – and we don’t make progress there.

So, we extend those crucial conversation skills:

1. Observe and listen without reacting or judging.

2. Label each negative feeling or objection that you hear expressed – but not in a judgmental way, in a descriptive way (itsounds like you’re frustrated, it sounds like we don’t agree on this element)

3. Then replace that with a positive, compassionate, and solution-based thought. (what might help us make progress? What do you need to resolve this)

Now I know that that sounds super rational. And that we’ve already learned that a combination of cognitive bias and fight or flight reponses can make this rationality difficult – so how do we manage to act like this? The best tip I know is that if you think you’re heading into the zone of uncomfortable debate, prepare for it.

Voss suggest starting your preparations with an ‘Accusation Audit’. Imagine the worst things your counterpart might think or say about you. Address these as soon as you enter the discussion – it gets them out of the way (you probably think I don’t care about business goals, you probably think I’m not interested in engineering complexity).

Try and avoid saying “I understand”, just saying the words don’t demonstrate understanding and can breed resentment.

And it might sound counter intuitive – but encourage people in the zone of uncomfortable debate to say “no”. Saying no makes people feel less uncomfortable, but if it’s the right kind of “no” it moves you closer to resolving the big issue.

Giving your counterpart the right to say no helps preserve their autonomy and sense of control. So it might feel uncomfortable – but that is the point of this zone, so ask no-oriented questions. Compare “is this a good idea…” to “Is this a ridiculous idea?”

Being asked to say yes too soon makes people defensive So use no responses to mark out the boundary of what is making collaboration uncomfortable.

When you receive “no” responses it gives you something to navigate around…. You can then explore and solve the problem you now share together…

• What about this doesn’t work for you?

• What would you need to make this work?

• It seems there’s something here that bothers you?

The zone of uncomfortable debate is sometimes the only way to navigate disagreement so that we can make progress and get to the big issue. So we don’t want to stay getting no responses, but we want to be careful with the type of yes that we get. Voss says there are three types of yes repsonse:

• Counterfeit: Yes is used as an escape route (they want to say no but don’t feel like they can).

• Confirmation: Reflexive response to a question. Empty affirmation with no promise of action.

• Commitment: True agreement that leads to action

The best type of ‘yes’ isn’t a yes. It’s a ‘that’s right’

That’s Right represents wholehearted agreement. It is focused on the idea – the big issue, rather than a person or perspective in the way that “You’re Right” is – that’s usually a sign that there is still distance and places you in opposition

Steps for Triggering a That’s Right include:

1. Effective Pauses: encourage your counterpart to keep talking .

2. Minimal Encouragers: e .g . yes, OK, uh-huh, I see. This shows you’re paying full attention .

3. Listen and repeat back what you’ve heard .

4. Labels: Give feelings a name to identify with how they feel .

5. Repeat in your own words what your counterpart has said to demonstrate understanding .

6. Re-articulate meaning of what was just said and acknowledge the underlying emotions and needs in a summary.

So, let’s do that now, summarise what I’ve shared and point out two other observations:

- Invisible barriers make things harder – but they often do it in a way that is hard to spot, so they can be demoralising. Removing them increases efficiency and gives you more energy to do the things you want to do.

- Because invisible barriers are hard to spot – overcoming them might be the source of competitive advantage – other people are more likely to have missed them too.

- And finally invisible barriers are often the result of unconscious bias and prejudice – so there’s often a social justice benefit to improving the way you think about and challenge them

Throughout this talk I’ve been advocating for the need to enter the zone of uncomfortable debate and armed you with some tools, techniques, models and ideas that might make your time in that zone more effective – even if it’s not much more comfortable.

There will always a zone of uncomfortable debate in any collaboration, but I think you can navigate it more successfully with these techniques. I also think there is one thing you can do to shrink this zone to make it easier to get to the main issues and make progress more quickly – and that is by building trust.

This is the trust equation. It describes the building blocks of trust… and fortunately I’ve given you tools to build this equation for yourself.

Humble inquiry helps you to balance all the elements in the equation – it avoids you pushing too hard for self-interest and opens up your ability to have meaningful interactions.

Crucial conversations give you the tools to build intimacy and credibility and getting the balance between listening, speaking and acting builds reliability.

Using some techniques from negotiation reinforces this and ensures that you don’t forget your own interests – whether that’s advocating for the user when other people are pushing business goals, or whether it’s creating the space to explain and expand your ideas alongside those of others on the team.

So – that might be the lesson of this whole talk. If we want to collaborate then we must build relationships of trust… because when we have relationships of trust, they’ll always be someone around to stop us making a horrible mistake – like the emperor in that story.

Leave a Reply