Here is the text of the talk I gave at UX New Zealand:

It’s great to be back at UX New Zealand, if only virtually.

I got the speak at this conference in 2016 and loved the feeling of community. Now I’m sat here, on my own, imagining you, sat in a room on the other side of the world – and it reminds me that reality is a bit of a tricky concept.

We can all experience what Lee Ross calls ‘naive realism’. That’s the tendency to believe that there’s ‘a knowable, objective reality’ out there for us all to experience on the same terms – if only everyone were as reasonable and rational as we are.

And at times, it’s been tempting to think that COVID, this global phenomenon, has created some sort of shared common reality. But we know that’s not quite true – medically, economically, emotionally and practically the experience has varied massively – we are not all affected in the same way.

In fact, COVID reinforces the fact that most of the time “reality” is really just a consensus which enables communication and collaboration.

This talk is about how we might consider that ‘consensus’.

It’s mainly focused on building, sustaining and using teams to achieve outcomes and provide support to their members. It’s also about innovation, the power of language, the need for design and in particular the usefulness of information architecture and an IA mindset.

And it’s secretly about the nature of reality itself. I want to convince you that reality does not come ready-made. It takes effort – and when we acknowledge that we can build creative, diverse communities and teams to shape reality together. So let’s get started.

1. Dan’s ambitious first chapter: What is reality?

You don’t have to be a seven year old with a new toy to know that sometimes, sharing can be hard.

I’ve been working from home for the past six months so the collaborative spaces I’ve experieneced have been – shared browser windows, shared documents, spaces shared in separation.

That is a profound shift… 20th century productivity suggested that the optimisation of space resulted in greater productivity. The assembly line suggested that products were assembled along rigid paths through discrete, sequential interventions.

1.1 Rowing or relay?

Even working in a design team I think we’re sometimes haunted by that idea of productivity being a relay race, rather than say a rowing race.

In a relay there are limited moments of collaboration and they can be optimised through repetitive, mechanistic practice… passing the baton. But rowers, in fact, all team sports require a level of sustained co-ordination.

I’ve been Creative Director for information architecture at the BBC for 5 years and the first thing I thought about when I got the role was what type of team should we be – relay or rowing or something else – football, with specialisation, improvisation and collaboration?

In my role I have two responsibilities when it comes to the team. I need to help make sure that collectively the IA team feel like a team and benefit from the practical and emotional support that comes from being part of a team. But those individuals also need to embed into other multidisciplinary production teams, with people with different perspectives, backgrounds and knowledge.

Those are two different environments – and each one requires a slightly different frame or mindset.

1.2 Frames and information architecture

We all carry our own unique perspective, experiences and knowledge with us into every experience.

This, often unconscious act of framing constitutes a big part of the information architecture of the experience – it provides our individual context. It’s easy to think that information architecture is just menus or sitemaps. It’s more than that. It’s the information that makes experiences make sense. So part of the IA of every experience is shaped by our personal perspective.

The other type of information architecture is environmental information architecture – it’s the IA that is embedded into an information environment – the arrangement and labelling of elements.

Thought this type you can pull the people within an environment towards more of a shared perspective. Cumulatively environmental signals can create pervasive shared perspectives like systemic biases and ideology.

The point is, every environment has meaning embedded in it, which along with our knowledge, beliefs and expectations shapes and directs our meaning making.

So.. two “types” of information architecture…

Individual information architecture is the personal perspective or frame that we bring to every experience.

Environmental information architecture is the IA that is embedded into an environment. It can be constructed intentionally or unintentionally. But It will almost always direct meaning-making and understanding.

These two interact. I think that is reality. Perception shapes our reality – and perception is made up of those two types of information architecture.

If we want to build effective teams – or any type of collaboration then we need to find ways of making sense together, creating shared spaces and pointing out where pre-conceptions, bias, prejudice and individual perspectives might make that more challenging.

2. You keep using that word…

I’ve said that perception is reality and I said that reality is a consensus? So how do you build an information architecture – or structures to enable shared perceptions – how does consensus come about?

2.1 Information, noise and distance

For most of us Covid has introduced some heightened level of physical distance. But I’m suggesting that without conscious effort ‘distance’ always exists between individuals and groups.. because sometimes, when we say a word it does not mean what we think it means, at least to the person hearing the word…

This is a super simplified model of information transfer.

It starts with an encoder, imagine me talking… I have some information to convey, I encode that, carefully designing my communication and choosing some form of technology to convey the information – I try to use words, pictures, sounds…

This is transmitted and the receiver grabs that information, decodes it and then interprets the meaning…

There are multiple points where interference can enter the system…

Sometimes decoding information and communicating effectively is challenging. The clarity of the signal is overcome by noise – or filters – which intervene. In my model these filters are the individual information architecture of a recipient.

When individual and environmental information architectures are incompatible – you experience a sort of cognitive dissonance…

2.2 Feedback conversations

Feedback conversations are a good example. They’re often coloured and shaped by emotions – which can frame and filter the meaning that each person has access to.

I bring my frame to the conversation. have access to my perception of the actions of the other person.

But I don’t have the same level of access to their motivations. Likewise, they don’t have direct access to my motivations.

They hear my words, through the filter of their expectations. I might trigger a threat response which further complicates the communication. The ‘noise’ in the conversation might increase and communication becomes more and more difficult.

You can point this out… talk about the gaps between behaviour, observations, impact and intent. Talk about automatic responses and introduce process-moves into conversations to navigate them more effectively. There is more on this type of thinking in this book.

The point is, it requires effort. To communicate and collaborate effectively you often need to put conscious effort into constructing shared realities.

3. Teams are shared spaces

3.1 Difference and diversity is a strength

Different perspectives always exist within a team – in fact, that’s the strength of a team – diversity of expertise, perspective and background results in more creative ideas. Diversity is the strength which underpins many successful teams. Those teams find a way to align while making the most of diversity.

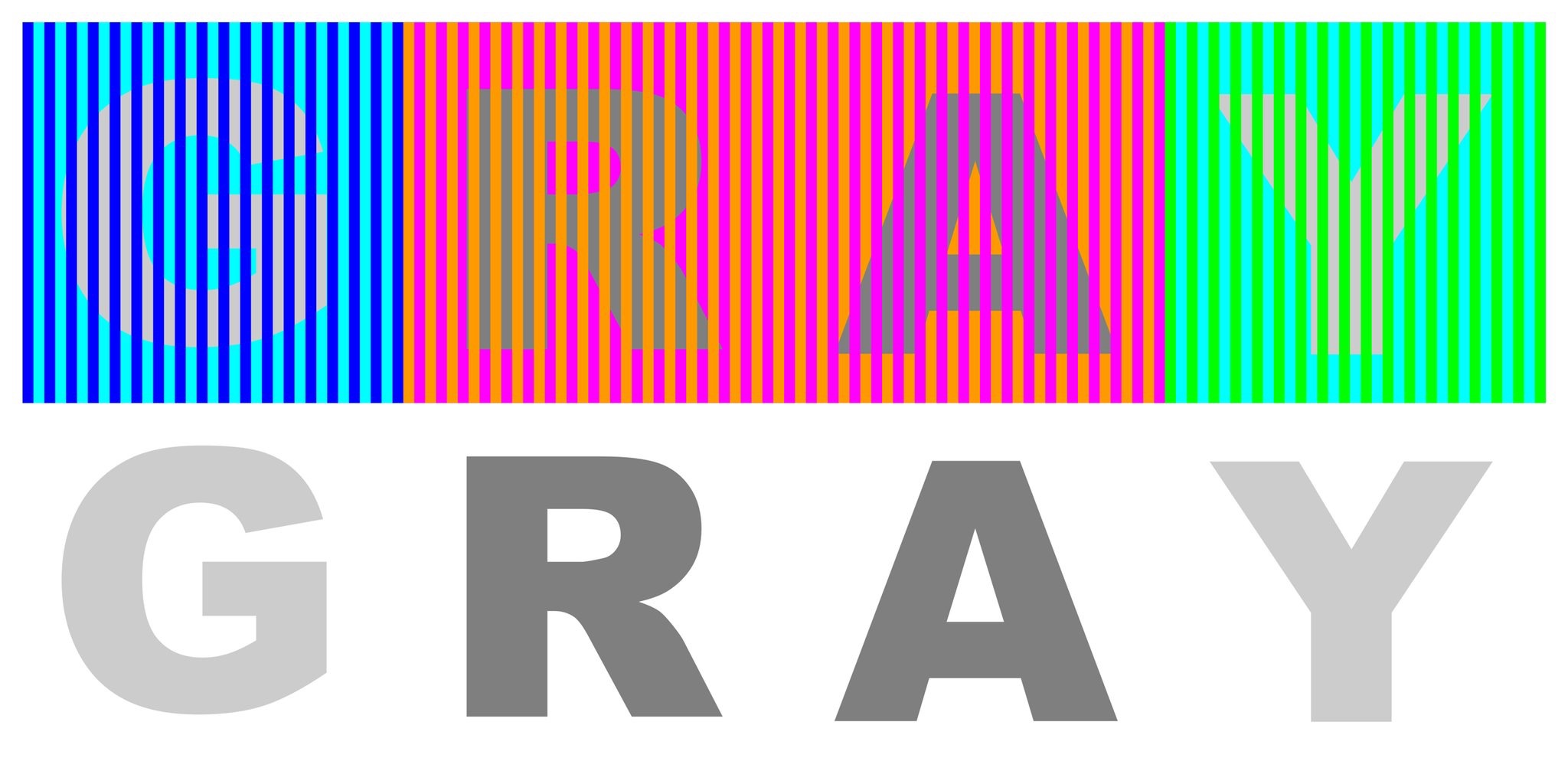

I think they do this by literally making the best of both worlds. In effective teams people can move between their specialist or individual perspective and occupy a shared space to explore meaning together. They can move back and forth to consolidate new information that comes from the team with their own individual world-view. This switching and sharing perspectives removes barriers that might otherwise trick you into seeing things as black and white when in reality most things are grey.

3.2 Boundary objects create shared landmarks

One way of helping with this is by creating what Carlile calls boundary objects – shared meaningful artefacts at the boundaries of knowledge – where things are least shared and most ambiguous.

These ‘objects’ act as a bridge between individual and shared perspectives. As designers, we know this. It’s why we put so much effort to concretise the abstract throughout the design process. We pour effort into creating shared definitions, or shared artefacts like wireframes, diagrams, stories.

These Boundary objects are likely to be useful in different ways to different people, but they are shareable. A prototype or a wireframe is a good example – visual designer will focus on one set of details, an IA another, an engineer another – but they do this while using the same object.

3.3 Teams must overcome more than knowledge gaps

So teams are shared spaces and they’re made so, at least partially through the creation of boundary objects, shared artefacts and experiences which bridge perspectives and knowledge boundaries between team members.

But the boundaries that trip up teams aren’t limited to knowledge. There are also cultural barriers that can make collaboration more difficult… because, even if you set off and establish shared definitions and areas of expertise, things change. Without shared values and behaviours within a team, a shared language often isn’t enough.

That’s one reason why the tools and rituals you use to form teams are so important. They create a set of boundary objects at the foundation of the team. They make implicit knowledge and assumptions within the group explicit – they are the start of creating a shared space which can then be expanded and reinforced through collaboration.

3.4 Kick-off template

There are lots of ways of forming teams and creating this first shared perspective… but we’ve been pretty heavy on theory so far so I wanted to talk through a practical example.

This is the template for a workshop that I ran remotely – shortly after our national lockdown, when we were forming a new team.

I started the session talking about shared experiences and values. I used a brilliant set of templates from the design team at Dropbox for this. They encourage team members to talk through past experiences and begin to trust each other.

After this first workshop I asked each individual to complete a ‘kick-off canvas’ which had a set of questions designed to expand that pool of shared meaning within the group.

It collected information that’s useful to me as I try to assign and co-ordinate work and also helps members to learn more about each other – their individual working preferences and how they might collaborate more effectively.

I could then use the inputs to talk about a shared vision for the project, build in development opportunities into the delivery and adapt my style of each team member.

I asked about working style preferences, comfort with ambiguity and conflict and about existing relationships within the organisation that might be useful for the project. And as we were all getting use to working remotely I also asked people to share their working patterns and whether they had other non-work commitments that the team should be aware of.

This template was inspired by the Team Canvas here:

And you can download my variation here…

But instead of just giving you a template, I also want to talk about the design of this template – because it is intentionally designed to create behavioural boundary objects, shared commitments to a set of behaviours.

So let’s look at five behaviours that I focused on, each taken from Patrick Lencioni’s Dysfunctions of teams…

3.5 Trust and psychological safety

The first barrier to effective teaming is a lack of trust…

Without trust it’s difficult to do anything. Members conceal weaknesses, mistakes, objectives and ambitions from each other. They don’t ask for help. There’s little honest feedback.

People are more likely to jump to conclusions about the intentions and aptitude of others without doing the work to understand them. People are likely to remain focused on a narrow area of responsibility.

Trust overcomes those barriers. It reinforces and energises teams, which makes building bridges across knowledge and skills easier. That’s why the team forming activity I described began with talking about past experiences and values – it opens up conversations designed to begin to build trust in a group.

Another name for trust is psychological safety.

“Psychological safety is a taken-for-granted belief about how others will respond when you ask a question, seek feedback, admit a mistake, or propose a possibly wacky idea”

– Amy C. Edmonson

Psychological safety and trust expand the shared space a team can occupy. It brings more types of questions and interactions into scope.

Without trust – fear can overcome a team. We’re hard-wired to avoid some conversations – those with challenge, judgement and feedback. This shrinks the types of conversations and learning opportunities that a group can support. When some conversations are off the table, you’ve already limited the potential range of solutions before you begin.

Which brings us to the second barrier to overcome a fear of conflict or challenge.

3.6 Conflict and Challenging Dialogue

Trust is critical because without it, teams don’t engage in honest debate. That creates two problems. It can stifle conflict, which can results in back-channel sniping or a build up of resentment.

It also just leads to poorer decision-making. You miss out on the full potential of the group because you’re unlikely to hear from all members.

Plus, meetings are boring without people questioning ideas and exploring perspectives… people spend their time doing interpersonal risk management rather than collaborating.

Conflict can be difficult to navigate. Productive conflict feels more like dialogue –Rather than always striking together to reveal weakness, which is sometimes necessary, you can also critique, reflect and revise together.

The key is that any topic is on the table, but it’s the topic that is discussed – rather than the people presenting them. When conflict and dialogue are mediated by trust and psychological safety it creates a learning climate that rewards curiosity. Otherwise, conflict is destructive and characterized by aggression and the possibility of humiliation.

Conflict can be tricky. But trust enables groups to rebound when things do get difficult.

In the template I asked directly how comfortable people were with conflict. This opens up a discussion within the group about preferences and styles connected to challenge and dialogue. We can then adopt practical techniques for conflict, built on top of our foundation of trust.

3.7 Commitment

Thirdly Lencioni talks about teams where a lack of buy-in prevents team members from committing to decisions they will stick to.

Without effective dialogue and challenge in a group you’re less likely to see commitment.

Without discussion and direction ambiguity can overcome a team. People revert to their own perspectives, which fragments the efforts and direction of the team.

And without commitment you just go round and round, having the same discussions again and again. People get frustrated.

Decisions direct people. They bring cohesion to the efforts of individuals. They enable you to learn from mistakes, because you have a shared sense of the desired intentions and outcomes. And they make changing direction easier – because you have a single, shared direction in the first place.

When teams don’t commit to a clear plan of action, peer-to-peer accountability suffers. Even the most focused and driven individuals hesitate to call out their peers if it’s not clear when and where actions and behaviours are agreed on.

I’ve used this grid in the past to facilitate conversations within a group about how we will make decisions. Introducing a language for decision-making helps to form that behavioural contract within the group so that expectations are aligned.

3.8 Accountability and Results

Lencioni’s final two barriers focus on a teams relationship to Accountability and Results.

If a team does not commit then it can’t be held accountable. That can create resentment and a slow march to mediocrity.

That inevitably leads to the fifth barrier – a team that’s not focused on results. That means that the team isn’t really a thing. You might start to see that individual ego and recognition becomes more important than collective team results.

Worse than that is when no-one cares about either the team or individual performance. The team stagnates, individuals fail to grow. Anyone with ambition leaves, anyone who stays becomes easily distracted.

In the template I made sure to ask about individual development and personal objectives – and by doing this openly they can become shared objectives and part of the purpose of the team – to help everyone to succeed personally as we work towards the objective the team was formed for.

With trust, constructive challenge, mutual commitment and accountability and a focus on shared objectives you can build and maintain high performing teams – and that might not just be in terms of “productivity”. During the early days of our lockdown and remote working it was hugely challenging to use the same style of direction, line management and support that worked when people were all located in the same buildings. The reliance on peer support and the team as a unit of support became more and more apparent. When they’re designed right, teams are also units of support as well as productivity.

3.9 Recap

So let’s recap…

– Reality is complicated. It can be warped by ideology, expectations and environmental design. We can build shared realities, shared information architectures in which things make sense to diverse groups regardless of background, perspective and expertise. It requires effort.

– That effort is worth it – diverse groups make better things.

– Communication is hard within any group. But teams can provide shared environments for collaboration – especially if you set them up correctly and build on foundations of trust and mechanisms for conflict resolution, commitment and accountability.

I’ve shared a few ways to start to build those characteristics. And you might have noticed that although some are designed to arrive at a sort of ‘shared contracts,’ teams aren’t really created through rules, guidelines, and slogans.

Teams are made through action and how you reflect on those actions – the successes and the failures. So to finish this talk I wanted to speak a bit about a mindset that can be valuable in teaming and leading teams – a way to shape those conversations during delivery and when reflecting on things. It’s what Edgar Schein calls Humble Enquiry.

4. The power of inquiry

“Too many would-be leaders forget about the power of inquiry, and instead rely on forceful advocacy to bring others along.”

If we ever needed a reminder that the world can sometimes be unpredictable, we just had 2020. COVID is also a reminder that wanting something to be true doesn’t make it true. You can’t just wish your way into a desirable outcome.

Sometimes, the best thing for a leader to do is to make a plan, communicate it clearly and stick to it. But at times of high uncertainty, ambiguity and unpredictability – asking and listening can be as important as deciding and telling. When you have a team of smart people around you – finding a way to ask questions and share information is the key to success.

That requires skills and the right sort of asking.

Some people weaponise inquiry – they use questioning as a tool to suppress and dominate others. This form of confrontational inquiry can see you insert your own ideas in the form of questions. Ever experienced that?

Another form of inquiry is diagnostic inquiry. It’s driven by curiosity. But it’s focused on a specific area or agenda. You steer and maintain the focus on this area.

And then there’s process enquiry, which gets meta and asks about the inquiry that’s taking place. We can see the impact of these different forms of asking through an example.

Compare:

Confrontational process inquiry – Are you upset, have I upset you?

Diagnostic process inquiry – What should I be asking you now?

Humble process inquiry – Is it OK to be talking about this today?

4.1 Humble inquiry

Humble inquiry is often the most useful form of asking – especially when you want to initiate or build relationships.

I’ve talked about how our individual information architecture shapes our perceptions – without conscious and intentional effort it can also direct our interactions, particularly at times of stress – like in a global pandemic.

What comes out of our mouth and our overall demeanour is deeply dependent on what’s going on inside our head. To be effective we need to learn what these distortions and impulses are.

We’re too often caught in this loop without considering it.

Prior experience forms expectation. This filters the data that we receive. We see and hear more or less what we expect, based on prior experience, or, more importantly, on what we hope to achieve. Our desires distort what we observe.

Then we react – often our initial reaction is an emotional one. That complicates things because often we fail to notice that emotions are part of us – rather than part of the situation or environment. A situation isn’t really tense – it’s the people who are tense.

Our Judgement is only as valid as the data it’s based on. And once we’ve made some kind of judgement, we act.

But this cycle is usually so quick that our actions are often short-circuited by our filters and biases.

Humble inquiry encourages us to stop – and consider observations. It slows our processes down and increases the chances of understanding what factors might affect our meaning-making and our ability to communicate with others.

5. Organising to learn

When we form a team, we get to decide what we care about.

In ‘Teaming’ Amy Edmonson talks about a way of working she calls ‘execution as learning’ – it involves organising to learn as well as deliver.

She argues that there are a few situations that are stable and predictable, where a ready-made, oven-ready solution can be rolled out.

But lots of the time, the world is more unpredictable than that.

We can still have plans – but we should treat them as experiments rather than dogma. And we should approach each other with care and curiosity – not only because it’s the human thing to do, but because it expands the range of possibilities we will see.

So… when you’re forming a team or part of a team ask yourself:

1. Share a goal – Is there a clear, shared goal that unites people towards a common purpose and motivates people to overcome communication barriers.

2. Cultivate curiosity – What mechanisms do you have to encourage questions and to make visible and concrete the invisible assumptions or barriers to collaboration that might otherwise trip you up?

3. Commit together – Is your decision making processes clear? Do people feel confident and supported enough to disagree when they think it’s important? And do they feel committed enough that when a decision has been made they commit even if they still disagree.

It’s been a pleasure to think about the UX community in New Zealand as I’ve written this talk. It’s been a sort of imaginative escape from working life in lockdown. And it occurred to me that I feel that about the teams I am a part of too – they represent shared spaces that I can go to be productive, to get inspiration and to recharge.

So, if you’re not part of that sort of team already, try to be a factor that creates that sort of team – or maybe use this event to make some friends in the community to get the same sort of benefits.

Reality does not come ready-made. It takes effort – and when we acknowledge that we can build creative, diverse communities and teams to shape reality together. So let’s get started.

Leave a Reply